We recently launched our first course on MillsWyck Academy. But before we did, I felt it prudent to get some feedback. I reached out to some of our most loyal clients and asked them to take the course and give us candid feedback and opinions of the course and what could make it better.

About the same time, my daughter came home from college and was able to attend an event where I was speaking. She offered me some… feedback. Unsolicited. Very direct. No mystery on what the point was.

In another situation, a person I would consider close endured some of my lesser personality traits, and when the conflict became unavoidable, let me know gently that my feedback, while correct and eventually appreciated, was given at the wrong time.

And in another situation, I was faced with the decision on whether to give someone feedback on something I observed that would make them better. I have open access to their life, but didn’t know them well enough to know how they might receive my feedback. It was a difficult decision. Do I risk offending and possibly hurting a relationship, or hold my tongue and likely leave them in a situation that will ultimately look very poorly for them?

And then there’s the scary prospect of asking for feedback. “What do you think of …?”

Feedback is a powerful and needed element for anyone that aspires to be better. But it’s intricately woven into the fabric of relationships, culture, and circumstance.

There are three places I lift insight from in how and when to give feedback.

First, I refer you to Carol Dweck, author of the life-shifting book Mindset. She describes two types of people: those with a fixed mindset and those with a growth mindset. Fixed mindsets believe that outcomes and character are predetermined and trying to change them is not worth the effort. As a result, people with a fixed mindset seek approval; they aren’t likely to want or seek opinions that are not like theirs. In contrast, a growth mindset believes that, with work and effort, anything is possible. Those with a growth mindset seek development. While it’s easy to think we would want to be driven by a growth mindset, it is much more difficult in practice. In giving feedback, it’s important to understand the mindset of the person receiving it.

My next source of wisdom is The Culture Map, by Erin Meyer. Ms. Meyer has studied all the countries on earth and how their culture affects their behavior. It’s my go-to recommended book for anyone doing business across cultures (I teach this to all my classes that are primarily international). One of the aspects she digs into is how cultures give and receive feedback. For instance, at one end of the spectrum are the Dutch, the most direct culture on earth. It is not uncommon for someone from that culture to tell you your outfit doesn’t match, your work is terrible, and your baby is ugly. And then they’ll want to go to dinner with you and laugh heartily. Nothing negative meant; just telling you the truth. Contrast that with Japan, where protocol and civility dictate that you never publicly tell anyone that their work is less than wonderful. If you did, the person is obligated to submit their resignation out of honor. Feedback instead might be given through nuance and suggestion. What you don’t say is sometimes more important than what you do say. But culture is not limited to country borders. Families, regions, and even individual personalities also dictate how people are able to give and receive feedback.

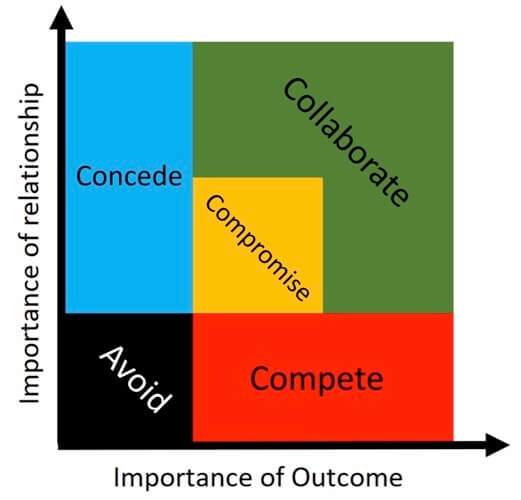

Lastly, I recently taught a workshop on dealing/communicating with difficult people. I took a model put forward by Alexander Hiam and modified it a little to come in line with my own experience. This model compares the value of outcomes against the value of relationships and stereotypes the behaviors (notably Western) that likely result. For instance, when the outcome doesn’t matter and I don’t care about the relationship, I just avoid the situation. If I get bad service and food at a restaurant, I don’t go back. But if my sister owns the restaurant, I have a different course of action to take, because the relationship matters. The best outcome is collaboration, where both parties work to preserve dignity and get an outcome that benefits everyone. What our culture promotes more often than not is competition, where only one can win (I’ll write in a later newsletter about how that view is flawed). Concession and Compromise are also options.

If you want to get better in your life, then feedback from a valued source is not optional. We would say that’s what a coach does. A coach’s assessments and suggestions get you to where you want or need to go. Feedback from someone who can make you better is nothing short of a gift. But culture, our own mind, and interpersonal relationships make it a hard gift to receive.

Here’s my advice, which is hard even for me to take.

- Feed off feedback. Not from everyone (Twitter is a bad place for advice), but from someone you trust. Approach them and share your reason for wanting the feedback – the outcome, and set parameters on how it should be given. But if you want to improve, the value of a coach and his/her feedback is not a point for debate.

- Temper your temptation to be offended. Consider the source. Most people who give feedback take a risk to do so. Consider their willingness as a gift and a commitment to your success and their style as a function of their culture. Just because you would have done it differently doesn’t make it wrong.

- Relate to the relationship. Jump into the outcome. Just because you have the authority to give feedback does not mean that you should give it. And just because you don’t know the person doesn’t mean you should withhold it. But it’s an ongoing tension that deserves thoughtful consideration. Perhaps the best advice is to think before you speak.

The feedback we received about our online course was amazing. We made some changes. The course is better as a result (see our announcement below!). My daughter was right. And thankfully, she is not a subscriber to this newsletter, because I’d never want her to see me admit that. Last week when I taught, I consciously made behavior changes that I think made me better. And the interpersonal relationships I risked are still intact, with both of us better for the interaction.

Communication Matters. What are you saying?

Want more speaking tips? Check out our Free Resources page and our YouTube channel.

We can also help you with your communication and speaking skills with our Workshops or Personal Coaching.

This article was published in the March edition of our monthly speaking tips email newsletter, Communication Matters. Have speaking tips like these delivered straight to your inbox every month. Sign up today to receive our newsletter and receive our FREE eBook, “Twelve Tips that will Save You from Making a Bad Presentation.” You can unsubscribe at any time.